서 언

재료 및 방법

식물 재료 및 재배 환경

광 처리

생육 조사

광합성 및 기공전도도 측정

Glucosinolate 함량 분석

통계분석

결 과

광질에 따른 생육

광질에 따른 광합성률 및 기공전도도

광질에 따른 glucosinolates 함량

고 찰

서 언

물냉이(Nasturtium officinale R. Br.)는 십자화과에 속하는 다년생 수생 초본식물로 맑고 차가운 물가에서 자라며, 유럽, 미국 그리고 아시아에 걸쳐 널리 분포한다(Cruz et al., 2008). 우리나라의 물냉이는 유럽 원산의 귀화식물로 “워터크레스(watercress)”로 불리지만 유럽에서는 프랑스명인 “크레숑(cresson)”으로 더 잘 알려진 향신 채소이다. 물냉이는 독특한 향기가 특징으로 예로부터 샐러드 채소로 이용되어 왔으며(Palaniswamy and McAvoy, 2001), 반수생성 식물로 종자번식 및 삽목 등을 이용하여 자연하천이나 온실 수경재배로 생산된다(Biddington and Ling, 1983; Manion et al., 2014). 미국 질병예방통제센터(Centers for Disease Control and Prevent)에서 칼로리당 영양밀도가 가장 높은 작물로 선정된(Di Noia, 2014) 물냉이는 비타민 C, B, E뿐만 아니라 Ca, P, K, Fe, Mg, Zn, Se, β-carotene같은 많은 미네랄과 glucosinolates를 포함한다고 알려져 있다(Zahradníková and Petříková, 2013). 식물에 함유된 glucosinolates는 풍미에 기여하고 항암 및 항바이러스에 효과가 있어 인간의 건강과 면역력 증진에 도움을 주는 물질이다(Mithen, 2001; Rodrigues et al., 2016). 특히 물냉이는 유익한 산화방지제인 2-phenethyl isothiocyanate(PEITC)를 많이 함유하는 것으로 알려져 있으며, PEITC는 특정 발암물질에 대한 신체의 저항능력을 증가시키는 것으로 나타났다(Palaniswamy et al., 1997; Alwi et al., 2010).

광원은 식물공장에서 식물 생산 시 중요한 제어요인 중 하나이며, 최근에 건설되거나, 검토중인 식물공장의 광원으로 발광다이오드(LED)가 가장 많이 적용되고 있다(Kang et al., 2016). LED는 가격 대비 우수한 성능, 상대적으로 높은 에너지 환산 계수, 다양한 스펙트럼, 비교적 낮은 표면 온도, 긴 수명 등 많은 장점을 가지고 있다(Kozai et al., 2016). 식물에 조사되는 광질은 다른 광수용체의 선택적인 활성화를 통해 식물의 생장과 발달에 영향을 미치는 것으로 알려져 있다(Schuerger et al., 1997). 특히 잎 세포의 엽록소 a와 b는 적색(600 ‑ 700nm)과 청색(400 ‑ 500nm) 파장의 빛을 효과적으로 흡수하기 때문에 적색과 청색광은 식물의 생장 및 발달에 필수적인 역할을 한다(Hopkins and Huner, 2004). 적색 LED는 생체중, 건물중, 초장, 엽면적과 같은 식물 생물체량 증가를 촉진시키는데 효과적이며(Johkan et al., 2010), 청색 LED는 식물 생장에 직접적인 영향 보다 엽록소 형성과 발달을 유도하는 것으로 밝혀졌다(Senger, 1982). 녹색광은 다른 파장과 비교하여 식물 조사 시, 반사율이 높은 광으로 식물 생장, 특히 광 형태 형성 및 광합성에 유용하지 않다고 여겨져 왔다(Johkan et al., 2012). 청색광 수용체인 cryptochrome은 식물의 하배축 신장을 억제하고(Lin et al., 1995; Lin et al., 1996), phototropin은 식물의 굴광성 및 카로티노이드 계통의 zeaxanthin의 형성에 관여하며, 이 외에도 기공 개폐와 형태형성에 직접 관여하는 것으로 알려져 있다(Briggs and Christie, 2002; Banerjee and Batschauer, 2005). 최근 보고된 바에 따르면 상추는 적청 혼합광 조건에서 전체 광량 중 적색광의 비율이 증가함에 따라 지상부 건물중이 증가하는 경향을 나타냈으며 청색광 비율이 7% 일 때 생육이 가장 좋았다(Wang et al., 2016). 아이스플랜트에서는 적색 단색광 처리와 비교하여 적청 혼합광 조건에서 생육이 좋았으며 특히 청색광 10% 처리구에서 가장 좋은 생육을 나타냈고 카르티노이드 함량은 적청 혼합광 조건과 청색 단색광 처리에서 높게 나타났다(He et al., 2017). 이렇듯 청색광은 생육과 2차 대사산물의 형성에 그 기능과 역할이 매우 큰 것으로 알려져 있으며 식물공장에 적청 혼합 LED를 적용할 경우 그 비율은 매우 중요하다.

최근 소비자의 식품 안정성과 기후변화에 대응 능력 향상을 이유로 많은 기업에서 식물공장 신규 진출을 모색하고 있다. 식물공장은 식물 생장에 중요하게 관여되는 광, 온도, 습도, CO2 농도, 양액의 EC, pH 등을 최적화 시켜 운영되기 때문에 식품의 안전성, 생산의 안정성, 고품질 및 연중 생산이 가능한 것이 특징이며, 고품질 대량생산을 안정적으로 달성하기 위해서는 환경 최적화가 매우 중요하다(espommier, 2010, 2013). 이와 관련하여 식물공장에서 케일 재배 시 수확시기를 조절을 통해 생리활성물질 함량을 증대 시킬 수 있는 연구 결과가 보고되었으며(Yoon et al., 2019), 로켓샐러드와 섬기린초 재배 시 각각 적색 LED와 청색 LED 광원에서 작물의 생육과 항산화물질의 함량이 증가되었다고 보고되었다(Lee et al., 2017; Oh et al., 2019). 특히 광원설계는 사전 예비 실험을 통하여 최적화를 이루어야 하고, 최초 광질의 선택은 향후 파장 조건을 변경하기 힘들기 때문에 매우 중요하다. 식물공장에서 안정적인 고품질 물냉이 생산을 위하여 양액 종류 및 양액 내 마이크로 버블을 이용한 연구 등을 보고한 바 있다(Choi et al., 2018; Bok et al., 2019). 이처럼 물냉이의 산업적 가치는 높지만 인공광원의 광질이 물냉이의 생장 및 품질에 미치는 영향에 관한 연구는 거의 보고되지 않고 있다. 따라서 본 연구는 식물공장에서 적색광과 청색광의 비율이 물냉이의 생육과 glucosinolate 함량에 미치는 영향을 조사하기 위해 수행되었다.

재료 및 방법

식물 재료 및 재배 환경

물냉이종자(Watercress, Asia seed Co., Ltd. Korea)를 원예용 상토(Bogeumjari, Nongwoobio Co., Ltd., Korea)가 담긴 162공 트레이에 파종하였다. 파종 후, 트레이는 온도 22 ± 1°C, 습도 60 ± 10% 상태로 유지하였으며, 형광등을 이용하여 광강도(PPFD) 170 ± 10mmol·m-2·s-1, 광주기 주간 16시간, 야간 8시간으로 설정하여 2주간 육묘하였다. 육묘기 본엽이 출현하는 정식 후 2주차에는 EC 0.5dS·m-1, pH 6.0으로 Hoagland 배양액(Hoagland and Arnon, 1950)을 이용하여 공급하였다. 본엽 4매가 전개된 같은 크기의 묘를 선발하여 순환식 담액재배 시스템이 설치된 소형 식물공장 시스템 (가로 3m, 세로 3m, 높이 2.5m)에 각 처리당 16주씩 정식하였다. 정식 후 Hoagland 배양액(2mM MgSO4·7H2O, 5mM Ca(NO3)2·4H2O,1mM KH2PO4, 5mM KNO3)을 사용하여 EC 2.2 ± 0.1dS·m-1, pH 6.2 ± 0.5로 유지하였다. 온도 및 습도는 주간 20/18°C(주/야), 60 ± 10%로 조절하였고 식물공장 내 CO2 농도는 외부공기 순환을 통해서 외부 공기농도로 유지하였다.

광 처리

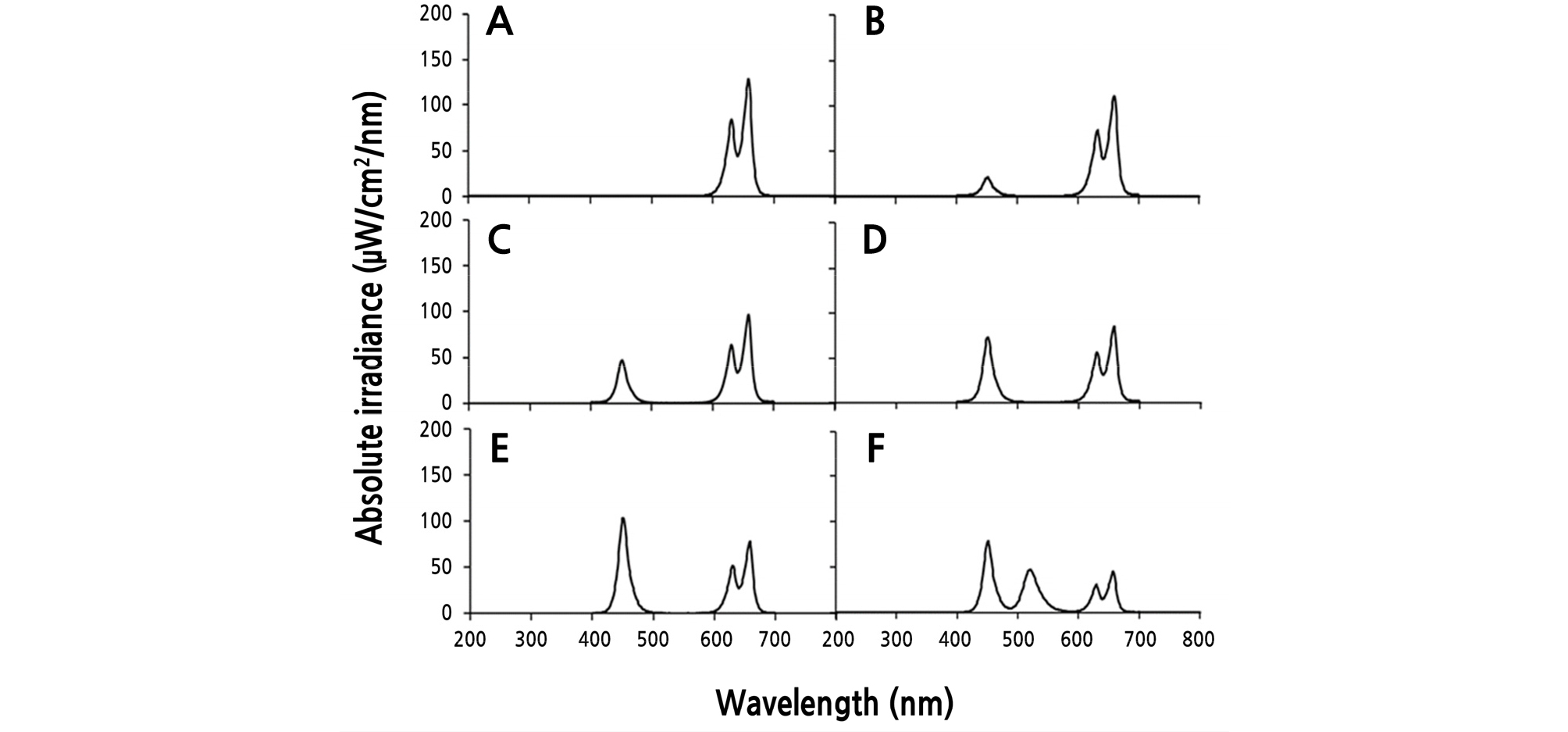

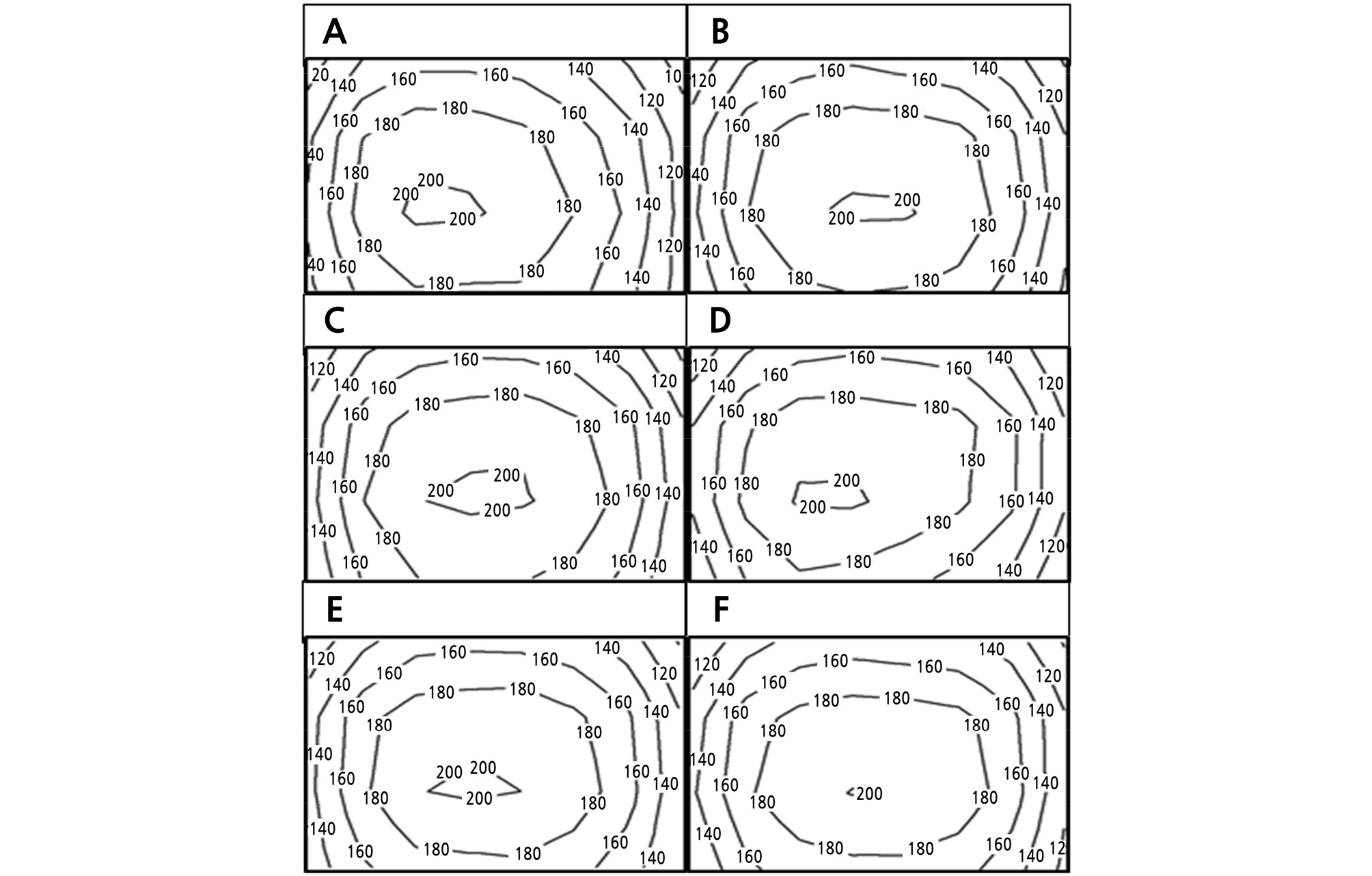

광질 처리에 따른 물냉이 생육 및 glucosinolates 함량 변화를 보기 위해 6가지 광질 처리를 설계하였다(Table 1). 첨두 파장을 2개 갖는 quantum dot 적색 LED의 경우 630, 660nm, 일반 청색 LED는 450nm, 녹색은 520nm인 발광 다이오드(SungGwang LED Co., Ltd., Korea)를 사용하였다[적색 LED는 quantum dot LED로 불리우는 쌍 피크 파장을 갖는 LED가 작물 생육에 유리하다는 보고(Choi et al., 2019)에 기반하여 본 실험에 적용하였다.] 각 광원의 비율 조합은 파장별 광합성유효광량자속밀도(PPFD: photosynthetic photon flux density)를 기준으로 각각 R10(Red:Blue = 10:0), R9B1(Red:Blue = 9:1), R8B2(Red:Blue = 8:2), R7B3(Red:Blue = 7:3), R6B4(Red:Blue = 6:4), R1B1G1(control, Red:Blue:Green = 1:1:1)으로 설정하였다. 각 처리의 스펙트럼 분포는 분광측정기(LI-1800; Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA)를 사용하여 측정하였다(Fig. 1). 모든 처리는 광량자 센서(LI-190, LI-COR, Lincolin, NE, USA)를 이용하여 광강도 200 ± 10mmol·m-2·s-1, 광주기는 16/8h(주/야)로 설정하여 2주간 재배하였다(Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Spectral data for various combinations of red (R), blue (B), and green (G) light-emitting diodes. The spectral data were acquired from 32 points and the means are shown

Fig. 2.

Contour plot of photosynthetic photon flux density distribution on a plant canopy in various LED lights combinations (n = 32). (A) R10 (Red:Blue:Green = 10:0:0), (B) R9B1 (Red:Blue:Green = 9:1:0), (C) R8B2 (Red:Blue:Green = 8:2:0), (D) R7B3 (Red:Blue:Green = 7:3:0), (E) R6B4 (Red:Blue:Green = 6:4:0) and (F) R1B1G1 (Red:Blue:Green = 1:1:1).

생육 조사

정식 2주 후 물냉이 초장, 지상부 생체중, 지상부 건물중, 엽록소 함량, 엽록소 형광 5가지 항목을 하였다. 초장은 지제부로부터 생장점까지의 길이를 줄자를 이용하여 측정하였으며, 생체중, 건물중은 지제부를 절단하여 지상부만 전자저울(MW-2N, CAS Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea)을 이용하여 측정하였다. 건물중은 절단된 물냉이 지상부를 건조기(HB-501M, Hanbaek Scientific Technology Co., Ltd., Korea)에 넣어 80°C로 5일간 건조 후 전자저울(ARG224, Ohaus Corporation, USA)로 측정하였다. 엽록소 함량과 엽록소 형광 측정은 생장점에서 5번째 잎을 이용하였으며, 엽록소 함량은 휴대용 엽록소 함량 분석기인 SPAD meter(SPAD-502 Plus, Minolta Camera Co., Ltd., Japan)를 이용하여 3회 측정하여 평균값을 이용하다. 엽록소 형광은 휴대용 형광 분석기 FluorPen(FP100, Photon Systems Instruments, Czech)를 이용하여 암적응을 위해 20분간 광을 차단시킨 뒤 5초 간격으로 2회 연속 측정하였으며 최대광화학효율을 알아보기 위하여 Fv/Fm[Fv/Fm = (Fm-Fo)/Fm(Fv: 형광변화값, Fm: 최대 형광값, Fo: 최소 형광값)]값을 측정하였다.

광합성 및 기공전도도 측정

정식 2주 후 광질에 따른 물냉이의 광합성속도, 기공전도도를 측정하기 위하여 광합성 측정 장치(LI-6400, Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA)를 이용하였으며 지상부 생장점으로부터 5번째 하위엽을 측정하였다. 광질에 따른 광합성 특성을 조사하기 위하여 투명 챔버를 이용하였으며 측정은 오전 10시 ‑ 오후 2시 사이에 실시하였다. 광합성 측정시 챔버 환경은 기류속도 500mmol·s-1, CO2 농도 400mmol·mol-1, 엽온 23°C, 상대습도 60 ‑ 70%로 설정하였다.

Glucosinolate 함량 분석

물냉이의 glucosinolates 함량은 HPLC(High Performance Liquid Chromatogram)를 이용하여 분석하였다. 정식 2주 후 물냉이 지상부를 Freeze-dryer(TFD5503, ilSinBioBase, Korea)를 이용하여 동결 건조 후 막자사발로 분말화 하였다. 2.0mL eppendort-tube에 분말시료 100mg씩 평량하여 70%(v/v) boiling menthanol(1.5mL)를 넣고 진동혼합(vortex) 처리 후 70°C 항온수조(water bath)에서 5분 동안 넣어 조(crude) GSLs를 추출하고 원심분리(12,000rpm, 10min, 4°C)한 후에 상층액을 추출하였다. 이후 식물체 내 glucosinolate 함량 분석방법(ISO, 1992)을 기준으로 inertsil ODS-3 column(150·3.0mm i.d., particle size 3mm)을 장착한 HPLC(1260 Infinity Series, Agilent Technologies Inc., USA)를 이용하여 sinigrin을 표준물질로 gluconasturtiin, glucobrassicin, glucosiberin, 4-methoxyglucobrassicin, glucohirsutin 각각의 response factor 값을 곱하여 5종류의 glucosinolate 함량을 분석하였다(Lee et al., 2015).

통계분석

본 실험은 완전임의 배치법으로 3반복 수행하였다. 생육 조사를 위하여 반복당 5개체를 측정하였으며, glucosinolate 분석을 위하여 반복당 3개체를 이용하였다. 실험을 통해 도출된 data에 대한 분산분석(ANOVA)을 실시하였으며(IBM SPSS Statistics 24, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), 각 처리 평균 간 유의성 검정은 Tukey의 다중검정법(p≤0.05)을 이용하였다.

결 과

광질에 따른 생육

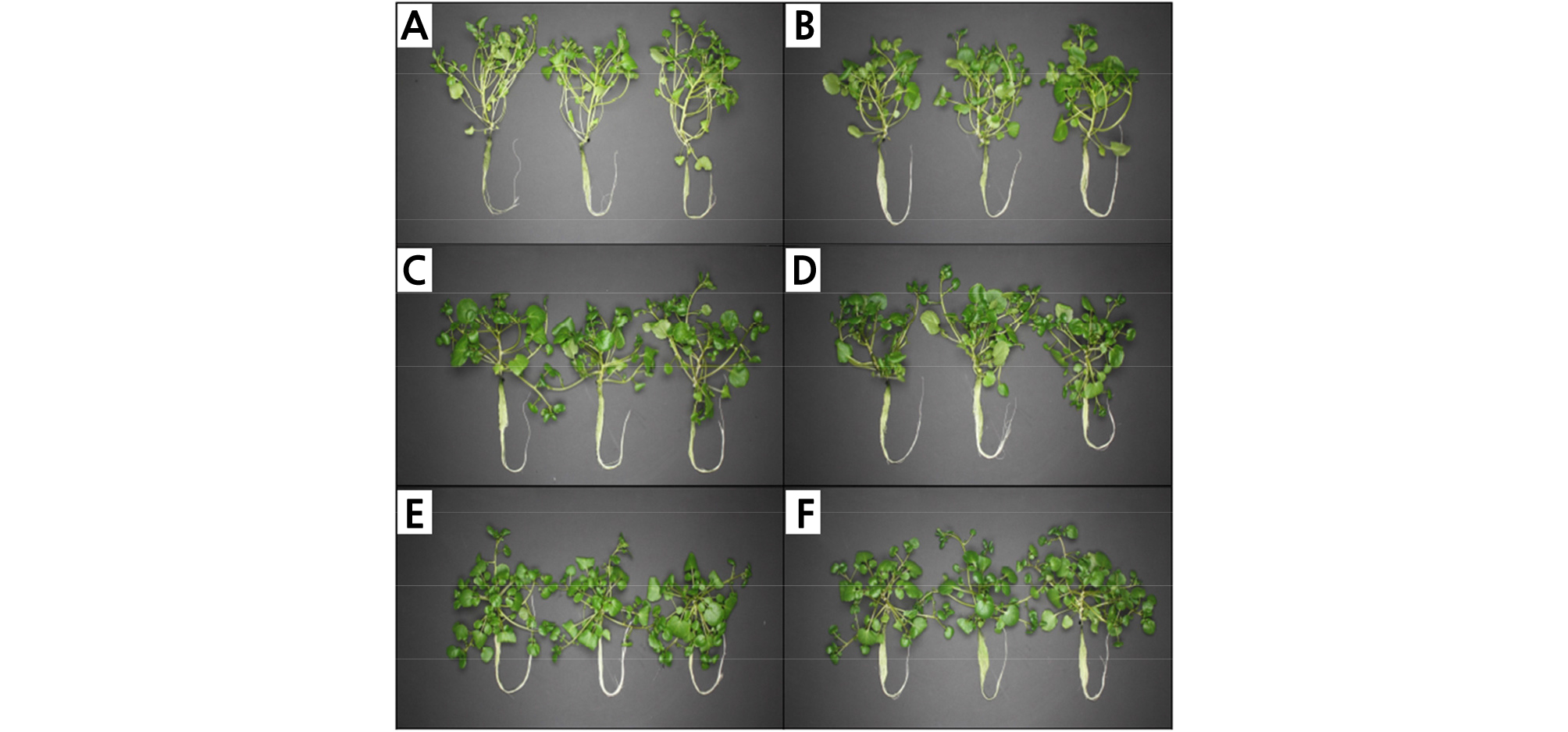

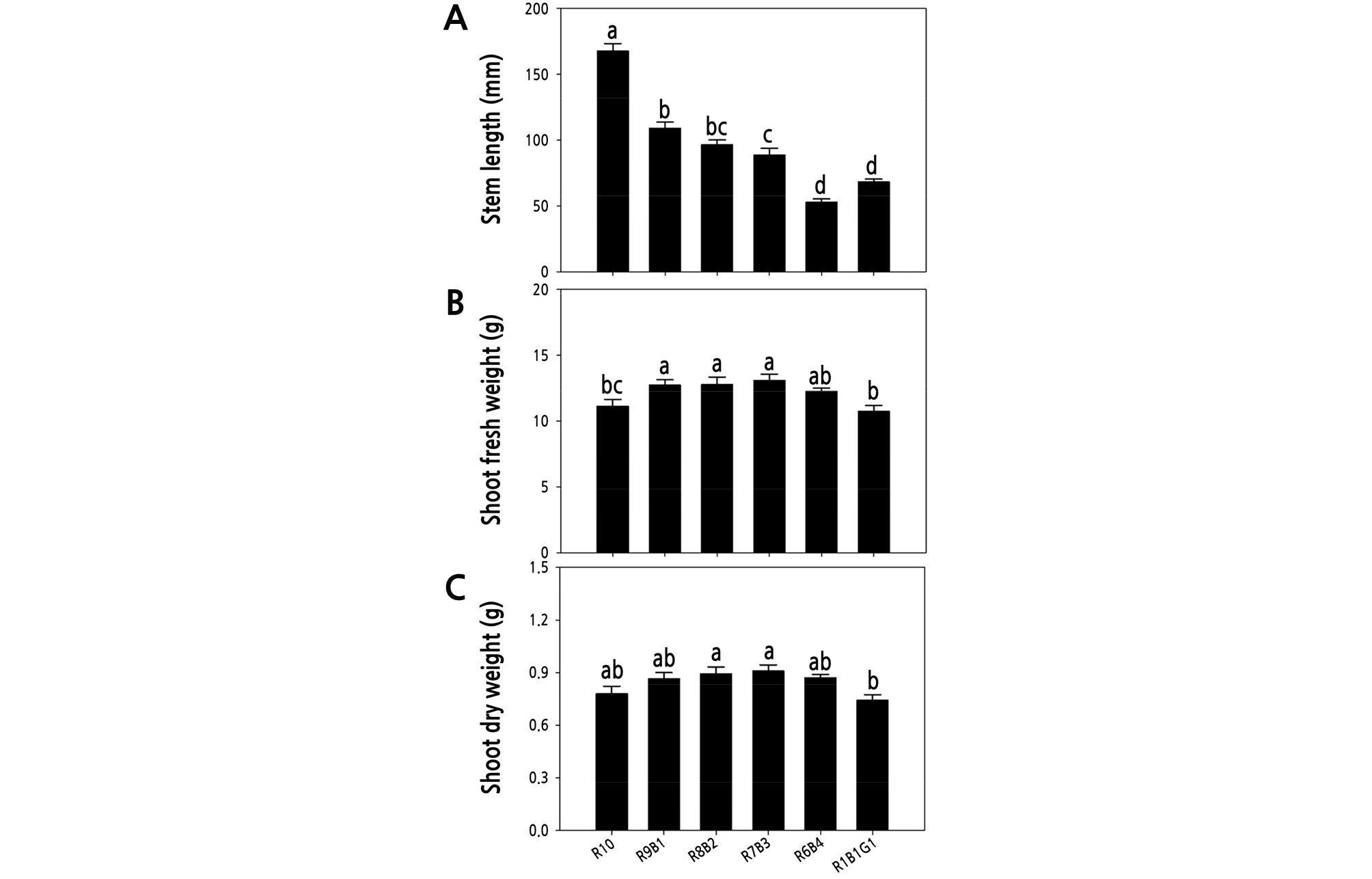

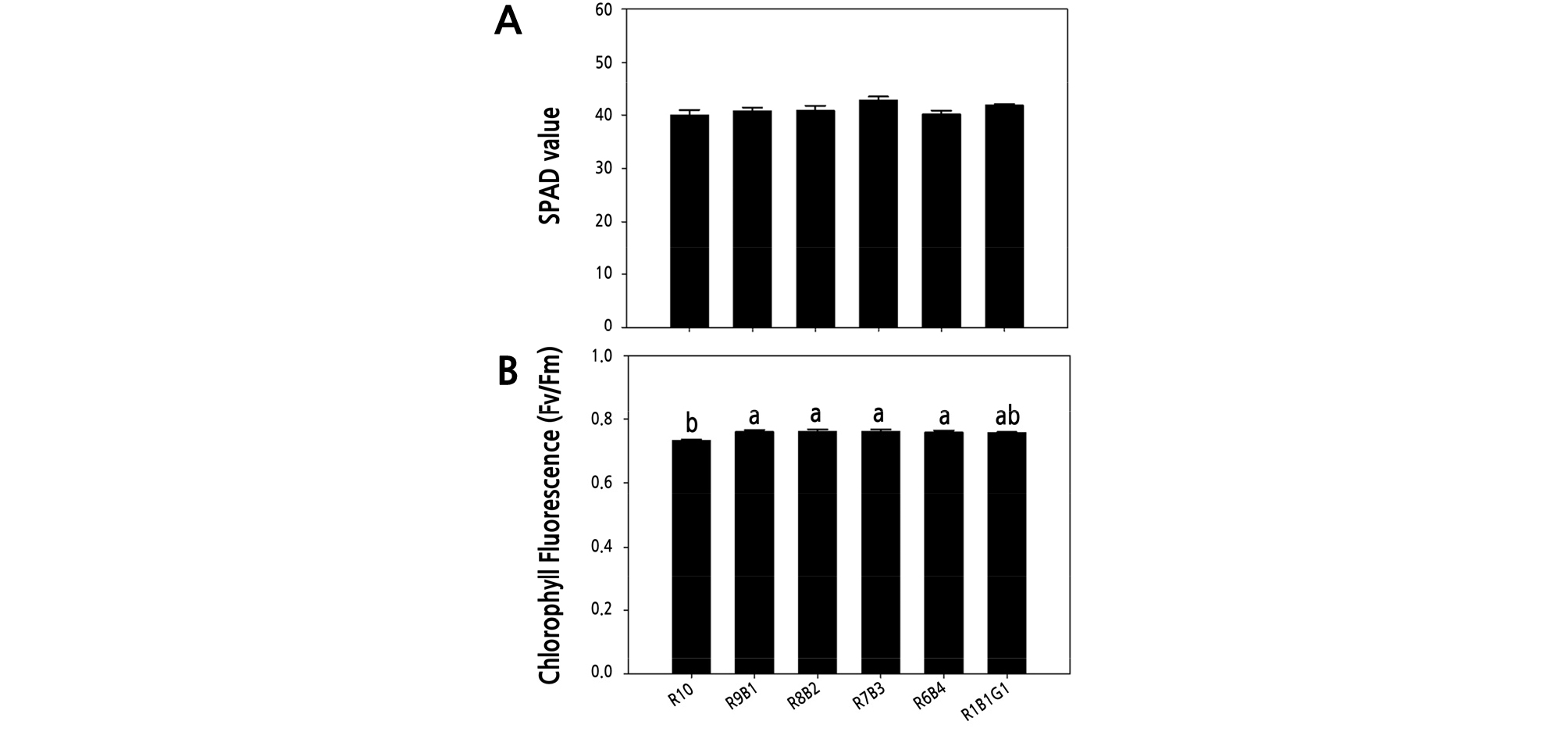

정식 후 6가지 광질 처리에서 2주 동안 재배된 물냉이의 초장, 지상부 생체중, 지상부 건물중, 엽록소 함량(SPAD), 엽록소 형광(Fv/Fm)을 조사하였다(Fig. 3). 초장은 R10 처리구에서 유의적으로 높았으며 청색광의 비율이 증가할수록 물냉이의 초장은 감소하였다. 적청 혼합광 처리인 R9B1, R8B2, R7B3, R6B4 처리구는 R10 처리구와 비교하여 초장이 각각 34.7, 42.5, 47.3, 68.8% 감소하였고 유의수준 5%에서 유의적인 차이를 보였다(Fig. 4A). 지상부 생체중은 R9B1, R8B2, R7B3 처리구에서 R10 처리구와 R1B1G1와 비교하여 유의적으로 높았으며, R6B4 처리구는 모든 처리구와 비교하여 유의적 차이를 보이지 않았다(Fig. 4B). 지상부 건물중 역시 적색과 청색 혼합 처리구인 R8B2, R7B3 처리구에서 R1B1G1 처리구보다 유의적으로 높게 나타났다(Fig. 4C). 휴대용 엽록소 분석기를 이용한 SPAD 값은 모든 처리구에서 유의적 차이가 없었으며(Fig. 5A), 엽록소 형광값(Fv/Fm)은 적색광 R10 처리구 보다 청색광이 혼합된 R9B1, R8B2, R7B3, R6B4, R1B1G1 처리구에서 유의적으로 높았다(Fig. 5B).

Fig. 3.

Nasturtium officinale grown under different LED light treatments for 2 weeks after transplanting. (A) R10 (Red:Blue:Green = 10:0:0), (B) R9B1 (Red:Blue:Green = 9:1:0), (C) R8B2 (Red:Blue:Green = 8:2:0), (D) R7B3 (Red: Blue:Green = 7:3:0), (E) R6B4 (Red:Blue:Green = 6:4:0), and (F) R1B1G1 (Red:Blue:Green = 1:1:1).

Fig. 4.

Stem length (A), shoot fresh weight (B) and shoot dry weight (C) of Nasturtium officinale grown under various combinations of red (R), blue (B), and green (G) light-emitting diodes (LEDs) for 2 weeks after transplanting. The data indicate the means ± SE (n = 5). Different letters above bars indicate significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, using Tukey’s multiple-range test.

Fig. 5.

SPAD value (A) and chlorophyll fluorescence (B) of Nasturtium officinale grown under various combinations of red (R), blue (B), and green (G) light-emitting diodes (LEDs) for 2 weeks after transplanting. The data indicate the means ± SE (n = 5). Different letters above bars indicate significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, using Tukey’s multiple-range test.

광질에 따른 광합성률 및 기공전도도

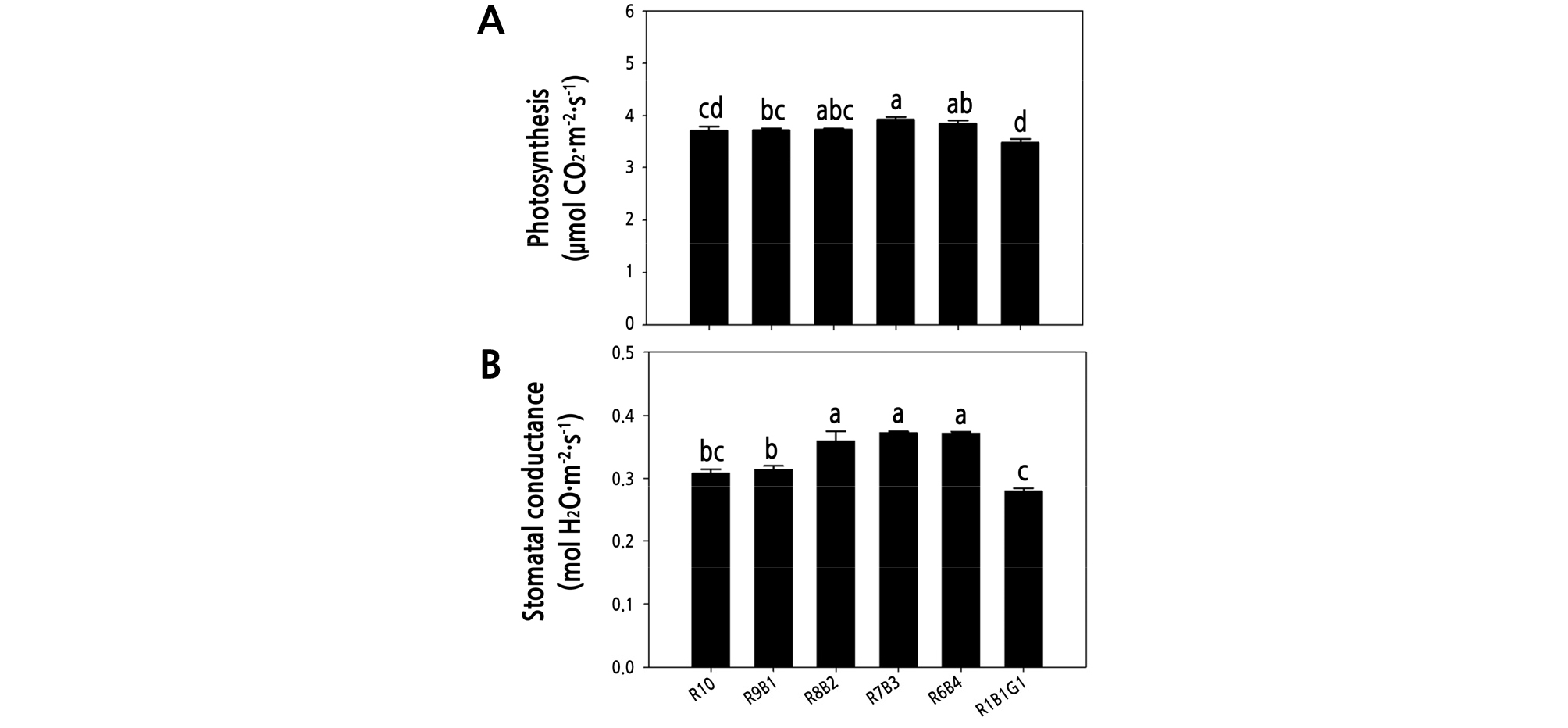

정식 후 6가지 광질 처리에서 2주 동안 재배된 물냉이의 광합성률 및 기공전도도를 측정한 결과 광합성률은 청색광의 비율이 증가할수록 증가하였다. 청색광 비율이 30%와 40%인 R7B3 R6B4 처리구의 광합성은 R10, R9B1, R1B1G1 처리구와 비교하여 유의적으로 높은 값을 나타냈으며, R7B3 처리구에서 가장 높았고 녹색광이 혼합된 R1B1G1 처리구에서 가장 낮았다(Fig. 6A). 기공전도도 또한 청색광의 비율이 증가할수록 증가하는 경향을 보였으며 R8B2, R7B3, R6B4 처리구는 R10, R9B1, R1B1G1 처리구와 비교하여 유의적으로 높은 값을 보였다(Fig. 6B). 가장 높은 값을 보인 R7B3의 기공전도도 값은 R10, R1B1G1 처리구와 비교하여 20.7, 33.4% 증가하였다.

Fig. 6.

Photosynthesis (A) and stomatal conductance (B) of Nasturtium officinale grown under various combinations of red (R), blue (B), and green (G) light-emitting diodes (LEDs) for 2 weeks after transplanting. The data indicate the means ± SE (n = 18). Different letters above bars indicate significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, using Tukey’s multiple-range test.

광질에 따른 glucosinolates 함량

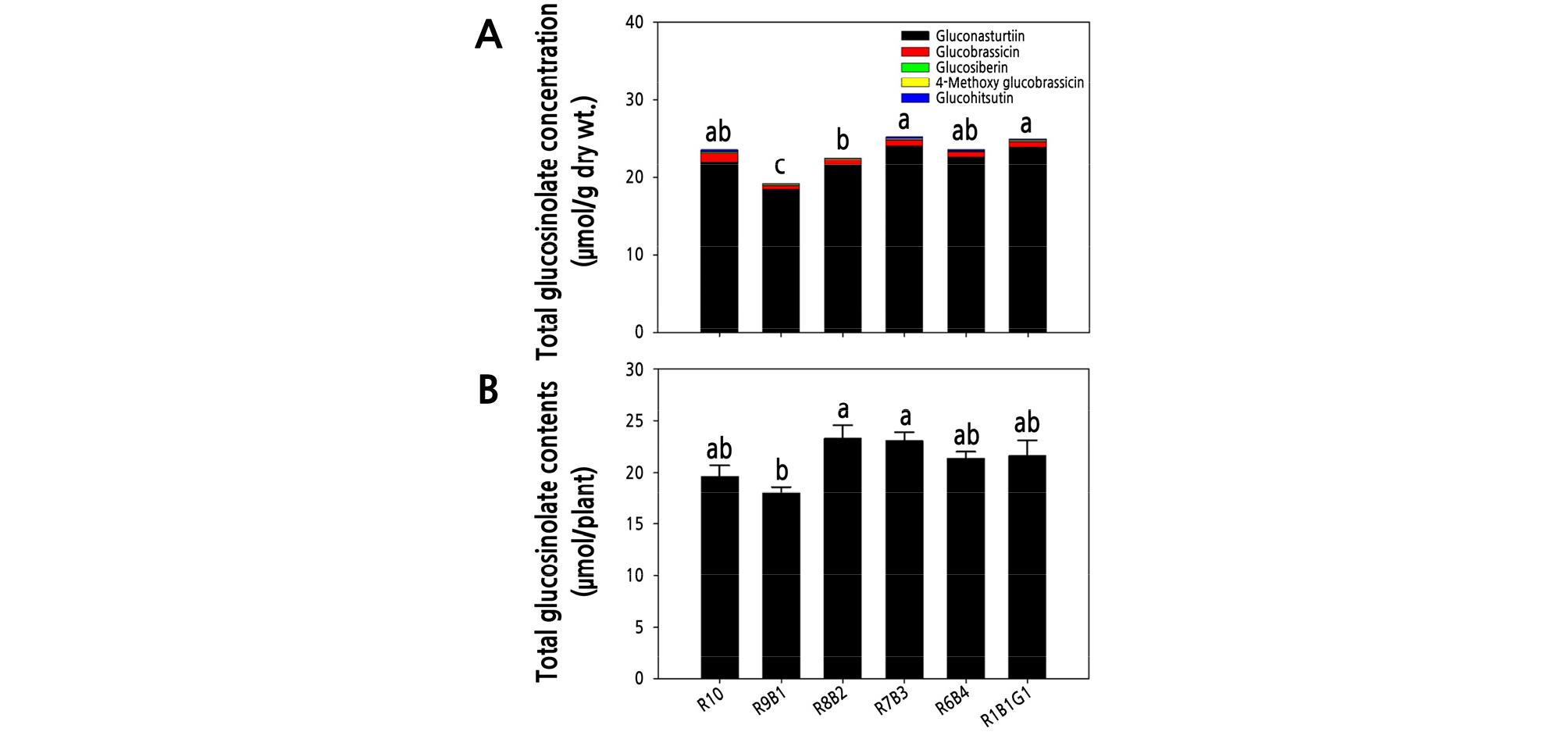

정식 후 6가지 광질 처리에서 2주 동안 재배된 물냉이 지상부에 함유된 glucosinolates 함량을 분석한 결과, gluconasturtiin, glucobrassicin, glucohirsutin, 4-Methoxyglucobrassicin, glucosiberin 순으로 많이 함유되어 있는 것으로 나타났으며, 전체 glucosinolates 함량 중 각 물질의 비율은 각각 95.2, 3.25, 0.63, 0.53 0.37%으로 나타났다. 물냉이 건물중 1g당 총 glucosinolates 함량은 R7B3와 R1B1G1 처리구에서 각각 25.29, 25.02µmol·g-1 DW으로 상대적으로 높았으며, R9B1과 R8B2 처리구에서 19.21, 22.55µmol·g-1 DW으로 유의적으로 낮은 값을 나타냈다(Fig. 7A). 각 처리구별 지상부 건물중 값에 단위 g당 glucosinolates 함량을 곱하여 식물체당 glucosinolates 함량을 구하여 비교하였을 때 R8B2, R7B3 처리구에서 각각 23.27, 23.03µmol/plant으로 높았으며, R9B1 처리구에서 17.95µmol/plant로 가장 낮았다(Fig. 7B). 같은 광강도 조건과 광주기 조건에서 광질의 차이에 따라 단위 g당 glucosinolate 함량이 최대 31.6% 차이가 났으며, 식물체 당 glucosinolates 함량이 최대 29.6% 차이가 났다.

Fig. 7.

Total glucosinolate concentration per unit of dry weight (A) (n = 3) and total glucosinolate contents per plant (B) (n = 5) of Nasturtium officinale grown under various combinations of red (R), blue (B), and green (G) light-emitting diodes (LEDs) for 2 weeks after transplanting. The data indicate the means ± SE. Different letters above bars indicate significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, using Tukey’s multiple-range test.

고 찰

피토크롬(phytocrome)은 적색광 수용체로 종자의 발아와 식물의 발달과 개화 등 식물의 다양한 생리 반응에 관여하며(Botto et al., 1996), 청색광은 상추의 잎 두께 촉진 등 잎의 형태형성 기능과 관련이 있다(Johkan et al., 2010). 이처럼 식물은 흡수하는 광수용체의 종류 및 조합에 의하여 작물에 따라 다양한 생리 반응을 나타내는데(Lee and Kim, 2014), 본 실험 결과 적색광 대비 청색광의 비율이 증가한 광조건에서 물냉이의 초장이 감소하는 경향이 나타났는데, 이는 오이 육묘시 청색광의 비율의 증가할수록 초장을 감소 시켰다는 연구 결과와 유사하였다(Hernandez and Kubota, 2016). 이와는 반대로 물냉이의 생체중과 건물중의 경우 적색광 대비 청색광의 비율이 증가한 광조건에서 생체중과 건물중이 증가하는 경향을 나타내었는데 이는 청색광이 형광등의 보광으로 사용될 경우 청색광이 없는 형광등 처리와 비교하여 상추 잎의 두께가 증가되었다는 이전 실험 결과(Ohashi-Kaneko et al., 2007)를 보아 이러한 반응은 적정 비율의 적청 혼합광에 의한 시너지 효과인 것으로 보이며, 본 실험 역시 청색광에 의한 영향으로 물냉이 잎과 줄기의 단위 면적당 바이오매스가 증가한 것으로 보인다.

녹색광은 적상추(Lactuca sativa ‘Outredgeous’), 무(Raphanus sativus ‘Cherry Bomb II’), 고추(Capsicum annuum ‘Fruit Basket’) 및 카놀라(Brassica napus ‘Westar’) 등에서 잎을 투과하여 작물 군락 깊숙한 곳까지 도달하는 것이 관찰되어(Massa et al., 2015) 잎 내의 광합성 조직에 더 깊이 관여할 수 있는 것으로 보고되었다(Brodersen and Vogelmann, 2010). 상추에서는 적청 혼합광 처리 시 일부 청색광을 녹색광으로 전환한 경우 지상부 생체중이 61% 증가하였으며, 형태형성, 광 투과율, 세포 분열 속도 역시 녹색광에 의해 증가하는 결과를 나타냈다(Son and Oh, 2015). 그러나 본 실험의 R1B1G1 처리구에서는 물냉이의 초장, 생체중, 건물중이 적색 혹은 적청 혼합광 처리보다 유의적으로 감소하였는데, 이는 적청 혼합광에 24%의 녹색광 보광 시 상추의 생육이 증가하였으나 50% 이상일 경우에는 생육이 감소하였다는 이전 연구 결과(Kim et al., 2004)로 보아 물냉이의 경우 33%의 녹색광에서도 생육이 감소할 수 있다고 판단된다. 또한 백색 LED 배경 광에서 녹색광을 보광할 경우 양상추의 초기 생장률이 매우 높게 나타났지만 파종 21일 이후에는 녹색광 보다 적색광 보광에 의한 생장률이 급속히 증가하였다는 결과로 보아(Mickens et al., 2018), 향후 물냉이 생육시기에 따른 다양한 파장대의 광원에 의한 연구를 통해 생산량 증대를 기대해 볼 수 있을 것이다.

SPAD 값을 통하여 식물에서 광질에 따른 엽록소 함량을 연구한 결과 오이, 상추, 시금치 등의 작물들의 경우 청색 단색광 처리시 엽록소 함량이 증가한다고 보고되었으며(Matsuda et al., 2007; Hogewoning et al., 2010; Johkan et al., 2010), 상추에서는 녹색 단색광 처리 시 엽록소 함량이 적, 청 단색광 처리보다 감소하였다고 보고되었다(Son et al., 2012). 아이스플랜트는 청색광을 포함한 혼합광 처리시 단색광 처리보다 엽록소 함량이 증가하였는데(Kim et al., 2016), 이는 본 연구 결과와는 상반되는 결과로 물냉이는 적색광 단독 처리와 비교하여 적청 혼합광처리에서 엽록소 함량이 유의적 차이가 나지 않는 것으로 보아 적청 혼합광의 시너지 영향이 적게 나타나는 것으로 판단된다.

엽록소 형광은 식물 스트레스와 관련하여 식물을 암상태에 방치한 다음 빛을 조사하여 정상적일 경우 0.78 ‑ 0.84 범위 값을 나타내는 Fv/Fm(변동형광값/최대형광값) 비를 이용하여 식물의 건전성을 추정할 수 있으며(Govindjee, 1995, 2004), 값이 높을수록 광합성 효율이 증가된다고 볼 수 있다. 또한 식물은 극심한 스트레스에 처하게 되면 광계 II의 불활성에 의해 광저해(Photohibition)가 나타나게 되고, 이로인해 Fv/Fm값이 감소한다고 알려져 있다(Schreiber and Bilger, 1993; Long et al., 1994). 본 실험 결과 물냉이는 적색 단독광 처리 시 적청 혹은 적청녹 혼합광 처리와 비교하여 Fv/Fm이 상대적으로 낮은 값을 나타내어 적색 단색광 처리 시 물냉이의 광이용 효율이 감소한다는 것을 간접적으로 보여주었다. 토마토 육묘 시 적색광 단독 처리보다 적청색 또는 적청녹색광 처리 시 더 높은 값을 나타낸 이전의 연구(Xiaoying et al., 2012)와 동일한 결과를 나타내어 적색 단색광 조사는 식물에 스트레스 인자로 작용하여 엽록소 형광을 감소시킬 수 있는 것으로 보인다.

물냉이의 광합성률과 기공전도도 결과는 적색광 배경에 청색광을 보광 할 경우, 밀의 기공전도도 증가와 더불어 광합성률이 증가하였다는 결과(Goins et al., 1997)와 일치하였다. 하지만 토마토 육묘 시, 적색 단독 처리보다 적청 혼합광과 적청녹 혼합광 처리 시 광합성률과 기공전도도가 증가하였지만(Xiaoying et al., 2012), 본 연구에서는 녹색광이 포함된 처리구에서 광합성율과 기공전도도가 가장 낮게 나타났다. 이는 식물은 단색광 처리 시 투과 파장이 좁아 광자 불균형이 초래되고, 이로 인계 광계 I 및 광계 II 반응이 불안정해져 식물체 내 전자 전달 연쇄 반응이 변한다고 알려져 있으며(Tennessen et al., 1994), 단색광에 노출된 식물에서 광계 II의 상대적 양자 효율이 감소하기 때문에 혼합광과 비교하여 단색광에서 광합성율이 감소한것으로 판단된다(Sager et al., 1982). 청색광의 경우 고등식물에서 종에 따라 적색, 청색 광수용체의 상호 작용에 의해 광합성률이 촉진되거나 억제될 수 있는 것으로 보고되었는데(Kim et al., 2004), 본 연구 결과 적청 혼합광 처리 시 청색광의 비율이 증가함에 따라 광합성률이 증가하는 경향을 나타내었다. 또한 적청 혼합광에서 청색을 녹색광으로 전환된 경우에도 물냉이의 생육과 광합성률은 정의 상관관계를 나타내었다. 하지만 상추에서는 적청 혼합광에 녹색광이 추가되었을 때 생육은 증가하지만 광합률율은 감소하였는데(Son and Oh, 2015), 이로 보아 녹색광에 의한 작물의 생육과 광합성률의 관계는 작물의 종에 따라 다르게 나타나며 녹색광을 제외한 나머지 광조건에 따라 달라지는 것으로 생각된다. 녹색광은 배경으로 하는 광환경 조건에 따라서 그 결과들이 다르게 나타나는데, 특히 녹색광은 청색광의 효과를 상쇄하는 것으로 보고되었으며(Folta and Maruhnich, 2007; Smith et al., 2017), 이러한 녹색광에 의한 반응은 유전자 분석에 따르면 cryptocrome, phototropin, phytocrome의 참여와 무관한 것으로 나타나(Folta, 2004) 녹색광에 의해 활성화되는 특정 광 수용체의 잠재적인 존재를 암시한다.

식물체 내 2차대사산물은 환경적, 생리적, 생화학적, 유전적 요인 등에 의해 영향을 받으며(Wink, 2010), 이중 광 환경은 식물의 2차대사산물 및 생리 변화에 가장 큰 영향을 주는 인자로 알려져 있다(Kopsell et al., 2004; Samuolienė et al., 2013). 특히 청색광의 비율이 증가함에 따라 식물 2차대사산물 증대와 관련한 연구 결과들이 보고되고 있다. Kalanchoe는 청색광 보광시 quercetin이 증가하였으며(Nascimento et al., 2013), 어린 잎 상추에서는 청색광이 증가함에 따라 anthocuanin, xanthophylls, β-carotene이 증가하였고(Li and Kubota, 2009), 브로콜리에서는 짧은 기간 청색광 조사를 통해 carotenoid, chlorophyll, glucosinolates가 증가하였다(Kopsell and Sams, 2013). 이러한 연구 결과들과 같이 본 실험 결과 역시 청색광의 비율이 증가할수록 물냉이의 2차대사산물인 glucosinolates 함량이 증가하는 경향을 나타냈다. 상추에서 적색과 청색 혼합광을 처리할 경우 청색 비율이 증가함에 따라 페놀화합물과 항산화능이 증가한다고 하였지만, 적색과 청색 혼합광에서 청색의 일부분을 녹색으로 전환할 경우 페놀화합물과 항산화능이 감소하였다(Son and Oh, 2015). 본 실험 결과 청색광의 비율이 전체 광량의 20 ‑ 40% 차지할 경우 글루코시놀레이트 함량이 단색 적색 처리구보다 유의적으로 증가하였으며 녹색광을 추가하여 처리한 경우에도 글루코시놀레이트 함량이 증가한 것으로 나타났다.

본 연구를 통해 물냉이 생육 및 기능성 물질 함량 증대를 위해서는 R7B3 처리가 가장 적합하였으며 녹색광 처리는 물냉이의 생육에 부정적인 영향을 미치지만 2차 대사산물 증가에 큰 영향을 미치는 것으로 나타났다. 향후 물냉이 생육에 보다 긍정적인 영향을 미치는 녹색광 비율을 조사하여 물냉이의 기능성 물질을 대량생산을 위한 추가 연구를 진행하는 것이 필요할 것으로 생각된다.